Due to performance issues and aging infrastructure SaskHistoryOnline will be migrated to a new system soon. Some disruptions may occur and the website will look different, but the material will remain. We apologize for any inconvenience.

A Glorious Ending to a Very Glorious: The story of Reginald John Godfrey Bateman

By: Eric Story

A small Irish boy entered the world on 12 October 1883, kicking and screaming as any newborn would, while gently being placed into his mother's arms. Frances Bateman and her husband, Godfrey, gazed upon their new creation, undoubtedly with love, pride, happiness, fear and all the other emotions that are felt when seeing one's child for the first time. They decided to name this small child––partially after his father––Reginald John Godfrey Bateman. They brought him to his new home in Listowel, where he would be raised and undoubtedly influenced by his sophisticated father who had a doctorate in law.

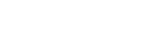

By April 1909 President Walter Murray of the University of Saskatchewan had contacted Bateman, asking if he would be interested in a job at the university. On 5 April, it was decided that he would meet with Robert Falconer, the President of the University of Toronto, who would attest to his character and ultimately determine if he would be suited for the position of Professor of English and French. In his short meeting with him Falconer saw a certain innocence in Bateman’s character. Perhaps this was because of his young age, for he was only twenty-five at the time. He went so far as to describe him as “a simpleminded young Irishman . . . without much experience of the world.” But simple-minded Bateman was not, as he would prove in later years. Nonetheless Falconer insisted ". . . he is the man we want." And so Bateman left his family behind in Ireland to enter a new phase in his life. He left the port of Liverpool aboard the Ottawa and arrived on 9 September 1909 in Quebec City. He then proceeded to Saskatoon to take up his position as one of the original four professors at the University of Saskatchewan.

In his first four years at the University of Saskatchewan Professor Bateman's development as a teacher can be described as a "long and weary road." This did not mean he was a poor teacher, but rather he was never able to attain the "ideal" towards which he was striving. He believed that all good teachers should never be satisfied with their work, for satisfaction meant the end of progress. He wrote: "As long as a man struggles, he is advancing; when he ceases to struggle, he has ceased to advance; and when he ceases to advance, it is almost certain that he has commenced to go backward."

Professor Bateman believed that literature was a form of art. Yet, he was frustrated by the belief, held by some, that reading and understanding literature was nothing more than a hobby. He declared that this notion was a "tremendous and . . . fatal misconception." If a teacher of literature were successful, the literature would transcend the pages on which it was written. Professor Bateman believed if we study literature, then, historically as well as artistically, our books will be to us not only works of art, but something more; they will become linked to long trains of association, which will carry us out into the life and happiness and suffering of our fellow men, and further still, out into the shock and sway of great world-movements, into the sphere where the Time-spirit weaves unceasingly the web of life. Ultimately, he argued "Literature . . . is the source of our highest development." If a teacher is able to communicate that to his or her students, humanity will be able to progress, for "it is by Art," he boldly stated, "and Art alone that Humanity progresses."

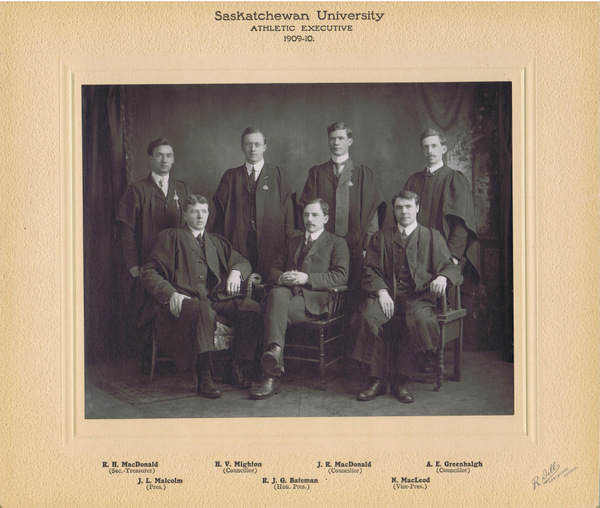

But whatever goals Professor Bateman had for himself and his students, they were at least temporarily put on hold when the call came for Canada's Second Contingent in September 1914. Professor Bateman resigned his position as Professor of French and English and enlisted in the 28th Battalion shortly after the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914. On the eve of his enlistment––25 October––Reg delivered a speech to the University Y.M.C.A. In it, he spoke of the "blessings" of war. Here is a short passage: History teaches that once a nation ceases to struggle or to be prepared to struggle for its existence, once it loses its military spirit and the willingness to fight to the death, if need be, for its national honour, its greatness invariably declines, and its growth ceases. What is arguably most important––and interesting––from this passage, is the parallels one can draw from it, and his earlier lectures regarding the teaching of English. Failure to progress leads to inevitable decline, not stagnation. War was a way for humanity to progress. After delivering his Y.M.C.A. speech, Bateman left Saskatoon for Winnipeg, the centre for the training of the 28th Battalion.

After arriving in Winnipeg in November, the first real test of the 28th Battalion was not what the soldiers had expected. In early May 1915 instead of going off to war themselves the officers sent off three other battalions ordered overseas before the 28th. According to Lieutenant Colonel Embury "Marching like Veterans with heads high, although in every heart there were the deepest disappointments, we marched back to barracks to wait and hope with never a sign of a breach of discipline, our metal tested to the extreme length of endurance." One can only imagine the disappointment Bateman must have felt when, just about to experience the "climax of human endeavour" as he described war, it disappeared right in front of his very eyes.

But the time for the 28th Battalion to embark on their journey overseas was not far off. By September they had reached France, and on the 25th they proceeded to Neuve Église. They immediately took over "the line" in the dark of the evening on 27 September with little knowledge of the trenches. Major Alex Ross of the 28th commented on the confusion of his battalion: when dawn broke, two companies, believing one another to be the enemy, proceeded to engage each other. Fortunately, no one was hurt, but it just goes to show the limited experience these troops had in trench warfare, and how disorganized the Allied war front was in this area of France. For the most part these very trenches were where Bateman would remain until he was recalled on 4 March 1916. The telegram he received that day read "return to Canada to a commission in Universities Battalion and Command Saskatchewan Company."

Upon his return, Bateman, on the anniversary of the Second Battle of Ypres, gave an address to a number of colleagues and returning soldiers. At this time the idealism that had been noticeable in his Y.M.C.A. speech was more difficult to recognize, for he was a changed man. It appeared that war had tempered his idealist beliefs. During his speech he applauded the enemy and was able to provide a glimpse into the life of a soldier in the trenches, saying that it was best described as "days of unendurable monotony and moments of indescribable fear."

An accurate portrayal of trench life would not be complete however, according to Bateman, without the humourous and the picturesque side. Humour was the only way to make trench life endurable. There was the irony of a broken rum jar being considered a greater calamity to the entire company than if the trench had been completely "blown to pieces"; and the satire of men arguing over the division of a pot of jam, while the Germans were peppering the trenches with gunfire. As for the picturesque, I best leave it to Bateman for an accurate description:

"I see the velvety blackness of the night, cut by streaks of light, as the flares go up continually along the front, as far as the eye can see . . . I see the flash and hear the bang of bursting shrapnel or the distant woosh and cr-r-rump of the high explosive; or there is the dull pop from Fritz’s line and high in the air a tract of light makes its way towards our trench. We hear the familiar whoo-oo-oo-oosh and we know that one of the dreaded aerial torpedoes is on its way; we wait with horrible suspense for the sickening thud and roar of the explosion, and wonder whether it has got anyone this time, and whether the next is coming our way . . . Then there are nights to look back upon around the battered old brazier in the dugout, when things were quiet, and we smoked a pipe or sang a song and thought of what we should do when we got that leave that never seemed to come."

By 1 November 1916, Reg had left the front line for England, and arrived there ten days later. In the New Year he was absorbed into the 19th Reserve Battalion and would stay with this unit through the winter in Bramshott, England. At the end of April 1917 he wrote to his brother, John, venting his frustration at being withheld from the battlefront. He wrote, "I simply cannot be content to stay here handling a job which absorbs scarcely any of my ability or energy, and which could be as well or better done by some one who is not fit to fight." Writing only days after the 28th Battalion––his former unit––had helped capture Vimy, he regretted ever leaving France in the first place, and taking for granted his time with the 28th. He concluded his letter by describing the glory of dying on the battlefield whilefighting for one's country:

"I might have been killed, but I was prepared for that, and I think there is no better way a man can die. It is comparatively seldom in the world’s history that a man gets the chance to die splendidly. Most deaths are somewhat inglorious endings to not very glorious careers. A War like the present gives a man a chance to cancel at one stroke all the pettiness of his life."

Although Bateman's idealism had faded in his most recent speech in the winter of 1916, his patriotism was still evident. His experiences in trench warfare had undoubtedly tempered his positive beliefs of war, but he still strongly believed in fighting for his country. And so Reginald Bateman did everything in his power to get back to France, to "finish what [he] began." On 6 June 1917 he reverted to the rank of Lieutenant in order to proceed overseas and by 30 June he had joined the 46th Battalion at Château de la Haie just outside the city of Lens in northern France. He was prepared for battle and also for death. He was ready to make the ultimate sacrifice for King and Country, but more importantly to him, for the improvement of society and a better world.

Wounded at the Battle of Lens on 21 August 1917 he underwent an extended recovery period, and returned to the 46th Battalion that winter at Bruay. By May 1918 the 46th, after having been in combat for over a month, received news of the recapturing of the Somme and Passachendaele by the Germans. According to a historian of the First World War, "There were tears of frustration in the eyes of many veterans," when they heard of the grave news. But with the significant losses of French soldiers and those of the British Empire, it was now up to the Canadian Corps to lead the final campaign to victory. On 7 August the 46th Battalion approached another destination on its seemingly endless journey, which would also be Bateman's final stop––at Gentelles Wood, near Amiens. The coming weeks would mark the beginning of the Second Battle of Arras.

On 3 September, after smashing through the Drocourt-Quéant Line and taking Dury––the 46th Battalion’s objective––the Germans heavily shelled and fired upon the city. It was 5:20 P.M. and Mac McDonald, a recently appointed Lewis-gun officer, was walking towards the Battalion Headquarters dugout when an officer waved him down. "I did a sharp right turn," exclaimed Mac, “"and as I did, a shell dropped in the entrance of the shelter." If he had not been waved down, he would have been hit by the shell’s burst. "This indeed was a manna from heaven," insisted McDonald. Perhaps for Mac, but not for Godfrey and Frances’ boy, the University of Saskatchewan’s first English professor, and one of the 46th Battalion’s "most popular officers," Reginald Bateman. Sadly he was killed instantly by the shell. The following day the chaplain of the regiment rounded up a small party of men who, "amid the roar of guns and screams of shells paid their last respects to a very gallant comrade and one of the best loved men in the Battalion": the son, the professor, the intellectual, the soldier, Reginald John Godfrey Bateman.

References

Bateman, Reginald. Reginald Bateman, Teacher and Soldier: A Memorial Volume of Selections From His Lectures and Other Writings. London: Henry Sotheran and Co., 1922.

Billington, Steve. “The University at War: Professor Bateman on the Blessings of War.” On Campus News. October 20, 1995.

Calder, Donald George Scott. The History of the 28th (Northwest) Battalion, C.E.F.: (October 1914-June 1919). Regina: Regina Rifle Regiment, 1961.

“Casualty Details: Bateman, Reginald John Godfrey.” Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Accessed March 1, 2013, http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/1565046/BATEMAN,%20REGINALD%2...

Kerr, Donald Cameron. “Bateman, Reginald John Godfrey.” Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online. Accessed May 1, 2013, http://www.biographi.ca/009004-119.01-e.php?id_nbr=7190.

McWilliams, James L. and R. James Steel. The Suicide Battalion. Edmonton: Hurtig, 1990.

Pitsula, James M. “Manly Heroes: The University of Saskatchewan and the First World War.” In Cultures, Communities, and Conflict: Histories of Canadian Universities and War, edited by Paul Stortz and E. Lisa Panayotids, 121-145. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012.

University of Saskatchewan Archives. University of Saskatchewan, President’s Office – WC Murray, A. General Correspondence, 6. Bas-Baw. General Correspondence – Bateman, G. Letter to Dr. Murray from Dr. G. Bateman. September 11, 1918, http://scaa.sk.ca/gallery/murray/search/index.php?ID=52797&field=keyword....

------. University of Saskatchewan, President’s Office – WC Murray, B. Name and Subjects Files, 8. Applications and Appointments (1907-1937) ¬¬– Bar-Bay, Applications and Appointments – Reginald Bateman. Untitled, undated letter, http://scaa.sk.ca/gallery/murray/search/index.php?ID=53544&field=name&se..., 8.

------. University of Saskatchewan, President’s Office – WC Murray, B. Name and Subjects Files, 8. Applications and Appointments (1907-1937) ¬¬– Bar-Bay, Applications and Appointments – Reginald Bateman. Letter to Dr. Murray from R. Bateman, June 3, 1909, http://scaa.sk.ca/gallery/murray/search/index.php?ID=53544&field=keyword....

------. University of Saskatchewan, President’s Office – WC Murray, B. Name and Subjects Files, 8. Applications and Appointments (1907-1937) ¬¬– Bar-Bay, Applications and Appointments – Reginald Bateman. Letter to Dr. Murray from R. Bateman, June 23, 1909, http://scaa.sk.ca/gallery/murray/search/index.php?ID=53544&field=keyword....

-----. University of Saskatchewan, President’s Office – WC Murray, B., Name and Subjects Files, 8. Applications and Appointments (1907-1937) ¬¬– Bar-Bay, Applications and Appointments – Reginald Bateman, letter to Murray from R.P.A. Falconer, June 21, 1909, http://scaa.sk.ca/gallery/murray/search/index.php?ID=53544&field=name&se....

------. University Secretary’s Office. Board of Governors Minutes. Board of Governors Minutes – 5 April 1909, http://scaa.sk.ca/gallery/murray/search/index.php?ID=58183&field=name&se....